Recently, we received an email from an associate in the real estate industry.

“I have a client purchasing a home built in 1988. The sellers stated that the prior owner mentioned a tank was removed before they bought the house. They don’t know if it was oil or propane. I requested an OPRA report, but am waiting for it to come back. Is it even possible for a home built in 1988 to have had a buried tank? The home inspector also noted evidence of prior oil heat but stated that searching for hidden or removed tanks is outside the scope of their inspection.”

Our Response

Yes — it’s 100% possible and, in many cases, likely. Most likely, the tank was an underground oil tank, although propane is possible if natural gas wasn’t available at the time. We’ve seen homes built as recently as the early 2000s that originally used oil heat.

After obtaining the property address, we determined that the home did have an underground storage tank (UST) removed, and it had leaked, resulting in an NJDEP case number.

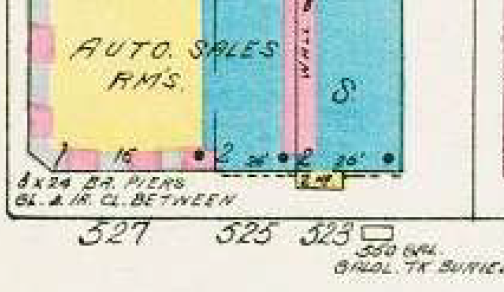

The OPRA (Open Public Records Act) request provided minimal information — only that a 500-gallon UST was removed in June 2014. Many people expect an OPRA to include detailed reports or test results, but it rarely does.

A “glass-half-full” person might assume the tank didn’t leak.

An experienced environmental professional would say: “Show me the documentation proving the tank did not leak.”

The Investigation Continues

Upon further review, we discovered that Curren Environmental had actually performed the remediation work years prior. (With thousands of projects completed annually, not every address immediately rings a bell!)

Fortunately, we were able to provide the NJDEP No Further Action (NFA) letter needed for the real estate transaction.

The Problem

The seller had no knowledge of the NFA or that it even existed. They only knew a tank had been removed — and some believed it was propane.

This is a perfect example of why, in real estate, you must trust but verify. Always confirm that what’s presented is accurate and supported by documentation before relying on it.

A Less Happy Ending

Not all cases end this smoothly. In another instance, we performed a tank sweep for a buyer on a beautifully renovated home listed at a premium price.

Our geophysical scan didn’t find a tank — but it did reveal groundwater monitoring wells, which typically indicate a history of contamination. Further research uncovered that the property once had an oil tank that leaked and was never closed out with the NJDEP.

The contamination had not been disclosed, and the sale fell through. One year later, the home still hadn’t sold and was being rented out. In this case, the seller — a flipper — had purchased and renovated the property without doing proper environmental due diligence, tying up significant capital in a contaminated property.

The Takeaway

Inspectors in New Jersey are not required to search for buried or removed tanks — but your clients rely on you for guidance. Recommending a tank sweep or environmental history review can protect your client from costly surprises and protect your reputation as a trusted professional.

Even honest sellers may be unaware of past tank leaks or remediation. The only way to uncover these issues is through Buyer Due Diligence — verifying records, performing scans, and reviewing NJDEP data.

Final Thought

When it comes to environmental concerns in real estate: Trust, but verify. Always do your due diligence.

This utility room houses HVAC equipment, a water heater & a washer and dryer. There are three typical causes of mold in this room. Mold was found; do you know where, the cause, and the fix? We did.

This utility room houses HVAC equipment, a water heater & a washer and dryer. There are three typical causes of mold in this room. Mold was found; do you know where, the cause, and the fix? We did.

Oil tanks belong to the property and if you buy a home with an oil tank you purchased all the costs associated with the oil tank, including oil tank removal, soil testing, and the most expensive part soil remediation (if required).

Oil tanks belong to the property and if you buy a home with an oil tank you purchased all the costs associated with the oil tank, including oil tank removal, soil testing, and the most expensive part soil remediation (if required).  Metal detectors beep if they find iron sand (a real thing), buried pipes, get too close to a metal fence or a structure with metal (yes homes have metal) or simply encounter buried metallic trash. GPR uses a screen so the geophysical technician can see the graphical image detected by the GPR antenna. Larger signals are tanks, smaller signals are usually pipes.

Metal detectors beep if they find iron sand (a real thing), buried pipes, get too close to a metal fence or a structure with metal (yes homes have metal) or simply encounter buried metallic trash. GPR uses a screen so the geophysical technician can see the graphical image detected by the GPR antenna. Larger signals are tanks, smaller signals are usually pipes.

The typical timeline for a Phase I ESA is two (2) to four (4) weeks. At Curren, we purchase historical records, which we usually receive within a week. When requesting public records (under the Open Public Records Act, or OPRA) from local towns or counties, we can expect a response within up to seven (7) business days. In New Jersey, for example, the law stipulates that a government agency must respond to an OPRA request no later than seven (7) business days after receiving it. Requests sent via email usually result in faster responses than those sent via mail. Day 1 of the response time starts the day after the custodian receives the request.

The typical timeline for a Phase I ESA is two (2) to four (4) weeks. At Curren, we purchase historical records, which we usually receive within a week. When requesting public records (under the Open Public Records Act, or OPRA) from local towns or counties, we can expect a response within up to seven (7) business days. In New Jersey, for example, the law stipulates that a government agency must respond to an OPRA request no later than seven (7) business days after receiving it. Requests sent via email usually result in faster responses than those sent via mail. Day 1 of the response time starts the day after the custodian receives the request.

![lClUW0yuSZuqaJQmdD7CjA[1]](https://www.currenenvironmental.com/hs-fs/hubfs/lClUW0yuSZuqaJQmdD7CjA%5B1%5D.jpg?width=227&height=171&name=lClUW0yuSZuqaJQmdD7CjA%5B1%5D.jpg)